Our Secondary Schools Adviser Catharine Driver explains why subject-specific literacy is so important at secondary school, and how we can help.

Pre-term CPD: a familiar scene

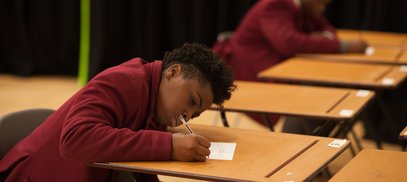

Picture this. It’s the first day of the school year and there’s a hall full of well-rested teachers keen to get back into the classroom. The school has invested a chunk of their precious CPD budget to start the year with a bang. “Today we are going to take a close look at literacy across the curriculum. We have a national expert in reading comprehension to work with you on embedding strategies into your new curriculum plans.”

And so the morning proceeds... generic comprehension strategies, skimming, scanning, close reading, perhaps a little reciprocal reading practice with A Christmas Carol or an historical recount. At lunch, the maths department gives some feedback: “Not subject specific enough.” The P.E. Key Stage 3 lead says: “Not relevant for my subject.” But the humanities team are talking animatedly how they can apply their learning to history and geography, and the literacy coordinator is relieved that she won’t have to lead all the twilight training in future.

So, what would help the maths or P.E. staff feel more enthusiastic about embedding literacy in their subject? How could you make that pre-term CPD in September a better day for them?

Why focus on disciplinary literacy?

The buzzword from the Education Endowment Foundation’s guidance Improving Secondary Literacy, is subject disciplinary literacy, also known as academic or subject specific literacy. It has been around at tertiary level for years under the banner of English for Academic Purposes (EAP) and is a well-resourced and active research area in many universities. Similarly, educators in the USA, Australia and New Zealand have been researching and being explicit about how language works in different subjects for a long time.

As part of curriculum delivery, all teachers need to understand how different subjects communicate knowledge through literacy, and how they can support students to read, write and communicate effectively in their discipline.

Understanding disciplinary literacy

Start by analysing need and build on existing expertise

So back to our secondary school...

Literacy in maths

Firstly, the maths team needs to spend some time thinking about how and what they read in their subject. There are textbooks of course, but every time we at the National Literacy Trust work with maths teachers, two things come up: word problems and vocabulary. So how can they support this type of reading and build students’ word knowledge?

It helps if maths teachers can be explicit about how they read differently from English or history. A word problem is not a story, a narrative; it is a text with its own generic features and form. Ahmed has not really been trying to work out which is the cheapest taxi from Oldham to Bury! Mathematicians need to read a problem slowly, closely, evaluating the significance of every word. The skimming and scanning techniques recommended for other subjects may not work for them. Grammatical words like “a”, “the” and “each” matter, but the character and setting do not.

Literacy and PE

What about P.E.? Sports teachers and coaches are often experts at modelling high-quality speaking and listening at KS3, but at KS4 P.E. presents advanced reading and writing demands in a scientific context. P.E. content knowledge is expressed through text, diagrams, photos and data as well as pitch-side analysis.

As well as thinking about subject specific reading practices, teachers of STEM subjects will also appreciate advice about how to teach vocabulary in their discipline. Think about how vocabulary used in formal writing differs from that of everyday speech. There are two ‘Englishes’; we acquire one in the home and the community and have to learn the other as a ‘second language’ as we move through school.

Think how the footballer talks in the thick of the game, all expletives and single word commands: pass, shoot, f*** off, goal! Compare that with the erudite match report in the broadsheet paper the next morning or the explanation of tidal volume in a P.E. textbook. Our everyday speech is full of Anglo-Saxon vernacular, but academic reading uses a vocabulary derived from Norman French, Latin or Greek. So, P.E. teachers, as well as maths teachers, may need to be more explicit about etymology and morphology when helping students learn and use new words.

Literacy leadership in subject disciplines

Finally, school leaders may want to think about what sort of literacy coordinator or consultant they need to train and mentor teachers with subject disciplinary literacy. Is the keen new English teacher really the best person for the job? Will they be confident to analyse and support reading in Maths and morphology in P.E and will they have the time to do so?

In 1975, the Bullock report recognised that every secondary school should develop a policy for language across the curriculum and employ an experienced linguist to work directly with subject teachers.

Unfortunately, this is a luxury few schools can now afford, so we now offer CPD courses about literacy in maths, science, geography, history and P.E.

Our support for disciplinary literacy

Our programme of secondary CPD provides expert-led training sessions planned jointly by subject and literacy specialists and designed to build your confidence and knowledge in how to teach literacy in your subject. We make the links between research, theory and practice explicit so that course participants leave with new understanding as well as practical strategies that work for their own subject.

We also offer a range of disciplinary literacy resources for premium member schools, such as Literacy in mathematics, Literacy in P.E., and Developing language and literacy in science.